Greetings fellow warlocks, today we delve deep in a small “How to make your own setting” guide, while we take a look at some super-good settings, and talk about the importance of settings in RPGs! Prepare yourself, this is a lengthy one!

What you’ll find in this blog post:

🪐The importance of Setting

🎲What makes a good Setting?

👀Let’s make a Setting

✍Making Settings, my method

Before we begin, I have to make two premises:

The first one is that this article is part of a series, so I recommend you read the first and the second articles if you wish to have more context.

If you’re here just to see what’s my Setting-making method, please feel free to skip both!

Second, and as said in the previous articles, this post is not saying rules don’t matter at all and that you should play every setting and idea in the same system. As a game designer myself, I think rules are important, and I would never tell you to play Cyberpunk 2020’s setting in D&D 5e.

With that out of the way, I think it’s time we take a look at…

THE IMPORTANCE OF SETTING

I do think we should focus more on Settings, rather than rules. Sure, rules are important, they are the tools that help us convey the Setting, after all. However, I think we should emphasize more the Setting, rather than the rules.

After all, think about some good memories you have of playing RPGs; I bet they are all about epic deeds, tragic deaths, and mystical lands you explored, rather than how good it was rolling a d20 and adding the modifiers.

Don’t get me wrong, I think a good system is necessary to enjoy a good setting, and that’s why in the previous article I listed some narrative-focused RPGs (that are also easy to hack).

However, ultimately, what gets me excited the most in a game is always the Setting, the vibes, the world I am thrown in. It’s the narrative.

Also, whether you pick or make your own narrative setting, you can use it on whatever system you prefer. You could even use it in different genre of games; nothing stops you in playing a wargame set in the same world you play your RPG!

So how do you focus on making a narrative Setting?

I think we first should analyze some super-good settings.

SETTINGS I FIND SUPER-GOOD

What makes a good setting?

While it’s always up to the one who enjoys them, I tried gathering some settings that I find very good, to find out what I like about them and therefore “what makes a good setting” to me.

Let’s first analyze these settings.

KAL-ARATH

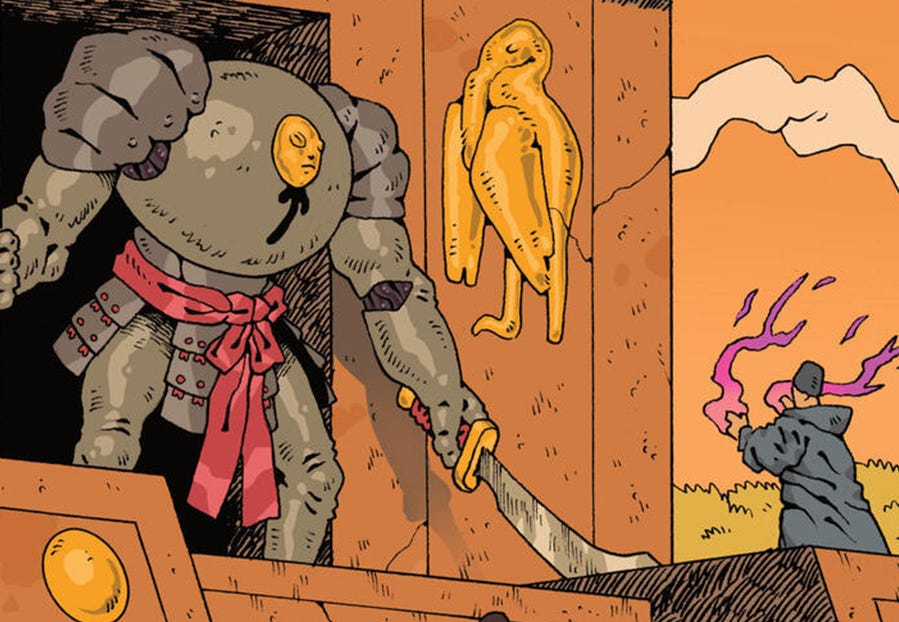

Lately I have been reading Castle Grief a lot, and I could not talk about settings without mentioning Kal-Arath.

Kal-Arath is a sword and sorcery setting, a savage steppe where blood-magic, demons, and the clashing of steel are business as usual.

Castle Grief wears its Conan and Frank Frazetta influences on a sleeve, and it really shows in Kal-Arath. You can sense it in the artworks, and you can sense it in the ruthless lore of the world.

One thing I really like is that the game itself tells you that if you want you can use just the setting (alongside its procedures and random tables) in whatever fantasy TTRPG you want.

Brilliant and honest.

DESERT MOON OF KARTH

The desert moon of Karth is a dusty mesa, where the only cities are surrounded by dangerous wastes where dreaded sandsquids terrorize the “Karthians”.

If your plans involve riding through the sands, drinking whiskey at a saloon, and discovering ancient orbital defenses, you’ll find yourself at home in Karth.

Silver Arm Press did an amazing job with this Mothership “space western” setting, and it shows beyond the cool artworks.

Once again, the game’s page suggests that this setting is perfectly usable with other TTRPGs that are not Mothership.

Cool, huh?

VERMIS

Now, off to something weird. Like, really weird.

Vermis takes place in dark, damp, and horrendous setting, that feels like a nightmare in old PC game graphics.

Vermis could not even be classified as a TTRPG setting in the first place, since it doesn’t feature any rules or tables.

It is however, a splendid artbook and world guide that can be totally used in whatever TTRPG. Hollow Press defines the book as a “lore game book”, and I think it fits, since you could use the lore inside the book as a base to run whatever narrative game you want. The effort in making this worldbuilding project by Plastiboo is phenomenal, and it shows.

We can safely say that this one went crazy on the vibes.

ELECTRUM ARCHIVE

I have spoken at great length about Electrum Archive in the previous articles, and I think it’s mainly because it does Setting very well.

Emiel Boven managed to convey, with his writing and his splendid artworks, a world that feels alive and it has its own identity.

One of its best qualities of its setting is the fact that by reading only a couple of pages you can already come up with a ton of interesting quests for your players.

So, now that we have found some cool Settings…

WHAT MAKES A GOOD SETTING?

I think the answer to this question can’t be set in stone, due to the nature of tastes and opinions.

However, I found that all the Settings that I like have a few things in common:

Strongly recognizable “vibes”: the themes, the concept, and the vision behind each setting are clear and engaging. Once I have shown you Kal-Arath, I doubt you’ll confuse its artworks with Electrum Archive.

Easy to describe: Want to describe and get your players interested in Desert Moon of Karth? Tell them “it’s Firefly meets Dune in a spaghetti western”.

Highly playable: How many quests come up in your mind when you look at the horror-inducing artworks of Plastiboo in Vermis? How many adventure hooks could you place in the world of Orn just by looking at the map in Electrume Archive? My answer is “a lot”.

Very compatible: Almost all of the settings I mentioned here discuss how you could totally use them in whatever game system you want, and that is because stats are easy to come up with when you have an entire book full of inspirations.

So to elaborate on this, for me, a great setting always has: a good concept, a good pitch, a good playability, and potential compatibility.

But how can we achieve this?

How can we make a good Setting?

LET’S MAKE A SETTING

I have my own method of worldbuilding (or Setting-making, if you want), which focuses on some of the points we discussed before, and it’s the result of many years of indulging in story-creation, lectures I attended, cool videos I found online, games I played, and all of my other interests combined.

And what’s beautiful about it is that means that my method of Setting-making will never be the same as yours.

So before we start, here’s my biggest advice:

THERE IS NO CORRECT METHOD OF WORLDBUILDING

The ways you can start creating a fictional world are countless. Some start by building a city, some start with the world’s history, while others will tell you that you should start by writing a story and build the setting around it.

And I guess they’re all right. There is no correct way of starting out.

What matters is that you start writing your setting, not where you begin.

Which brings us to my second biggest advice:

YOU DON’T NEED TOOLS FOR WORLDBUILDING

When someone asks “what are the greatest tools for worldbuilding?” online, expecting to get as answers “the greatest book on building worlds”, “the youtube lectures on how to never make a mistake when writing a world”, or “the obscure zine of prompts to build the next Middle earth”, I annoyingly respond with:

”A sketchbook, a HB pencil and some gel pens”.

The reason I do this is because most people get so caught in the web of absorbing and learning, stuck in an endless cycle of research before attempting to write… that they end up never writing anything.

So sit back and relax my friend, and just start.

Yes, there are a lot of interesting tutorials online on how to build specific aspects of your setting, like Hello Future Me videos on creating Religions, or professional lectures on worldbuilding from writers like Brandon Sanderson.

And I do think they are useful.

However, they are in no way “essential” for you to start building your own world. Heck, you don’t even need THIS article to start world building!

It’s okay to research for advice and writing aids, but don’t let that stop you or slow you down when creating a setting.

All you need is pencil and paper. Or Word if you do it digitally.

A scalpel and a cave rock if you are in Prehistoric times.

With that out of the way, here’s my own method of Setting-making.

MY SETTING-MAKING METHOD

As you may have guessed, this is not a series of prompt or a specific method on how to build cities, nations, or religions, since there are already a lot of good resources for that.

But rather a method (or a checklist) I use when I start a new Setting, that helps me keep my focus on the project. Hopefully, they may help you too in starting your own!

0.5) Write down your concept

Did you have an idea for a new setting? Well, then I suggest you write it down somewhere, in under 180 characters if possible. This may sound silly but narrowing down your idea to a couple of sentence will act as a guideline for yourself when you feel like you have lost track of your own objective.

Don’t get too caught up in coming up with something epic; even “Aliens in medieval world” may sound simple, but it actually leads to some great worldbuilding ideas. (It’s OLDMOON by Lupiron Press, by the way)

1) Gather your inspirations

Write down your inspirations for this new world, and they can be from all sorts of origins, from movies to books, from video games to real world events.

If it helps visually, go make a moodboard or a Pinterest board.

You will come back to these anytime you feel stuck and need some additional inspiration. They will also be handy later, when you’ll need an elevator pitch!

2) Themes and Pillars

Define roughly what are the common themes you’ll want to explore in your setting, even though they will not be the only themes featured in it.

You can also expand some of the “Pillars” of your concept.

For example, in Warhammer 40.000 one of the core themes is, you guessed it, war. Alongside that theme there are also tales of brotherhood, ignorance, and courage.

One of the “Pillars” of Warhammer 40k is the Warp, a parallel dimension where psychic powers and daemons come from.

Noting these down help you stay “in the box” of your setting, in case you need to refer to some concepts of your idea.

3) Do an elevator pitch

Elevator pitches are short and descriptive depictions of your setting. Not only they are the stronger version of your initial concept, they help you paint a picture to all of those who are not familiar with your world, be them players or publishers. It doesn’t have to be cool or epic, just descriptive.

It comes in handy to have some cultural references to explain it.

When I had to explain my game Hellgreen to my art team, I used “Imagine the videogame STALKER meets the Vietnam War, in a solo RPG”.

It wasn’t epic, but they immediately got the picture!

4) Do a “Bus ride pitch”

This is some sort of a stronger cousin to the elevator pitch.

Imagine this as the blurb you find on the back of a book.

This is what you’ll need to explain your setting to someone who’s interested in it, maybe grabbed by the tagline concept or by your elevator pitch.

I suggest you keep this from 250 to 300 characters if you can.

Use all the things you prepared until now: Concept, pillars, inspirations, themes. Try to distill everything under 300 characters!

5) Come up with a couple sample quests/stories

I saw this on a very interesting video by the legendary developer Tim Cain on how he builds world for his video games. He essentially asks himself a question:

”Can I come up with interesting quests for this game?”

You can do the same for settings. Come up with a couple of simple quests you would put in this setting. If they excite you, you are on the right path!

They also may come in handy for future random tables, who knows!

6) Come up with a plan

Okay, this may be the hardest one.

You have a world. It may not be very fleshed out, but it’s a world.

Now you need to vaguely plan what you actually need to play in this setting.

The reason I say you need to plan it is because it’s very easy to feel overwhelmed by the amount of stuff you need to do, or even worse you may feel like you are always in need to add something to your world.

Some call this “the worldbuilder’s disease”, I call it the “don’t look it’s not finished yet” problem.

To avoid this problem, you need to realize two important concepts:

-You don’t need to flesh out every single detail of your world.

-Sometimes it’s better if your world has holes that can be filled by Players/Game masters.

Knowing this, come up with a list of 4-5 things you want to detail before playing your games/publishing your setting on the internet.

This is your plan, and be sure to stick with it.

7) Don’t worry about system too much

As we said in the beginning, after all, systems are a tool to enrich and reinforce the narrative of your game. But what you’re working on now is the narrative, which is and will ever be the most important thing in your narrative games.

So yeah, don’t worry about systems too much, okay?

Are we done yet?

This pretty much concludes what I envisioned for this trilogy of articles on settings.

There are countless things I may have left out, like brilliant books filled with prompts and random tables, interesting systems, and useful videos, so pardon me for that.

But after all, one of the joys of Setting-making to me is both discovering and sharing, so I’ll leave you that.

With that being said, now my noble readers, the scepter of Setting-making is in your hands.

Go make a memorable Setting!

This article makes some great points about creating a setting. Silver Nightingale and I are just putting the finishing touches on our Kal-Arath Compatible setting book. It is called Al-Rathak: Tales of the Crescent Kingdom, and it has an Arabian Nights vibe. It also has sea exploration (think - Sinbad and his 7 Voyages). I think you would like it based on what you have said in this article.

I completely agree with you on this piece. Setting is the most important thing - it draws you into the game and keeps you there.